- Home

- David Eddings

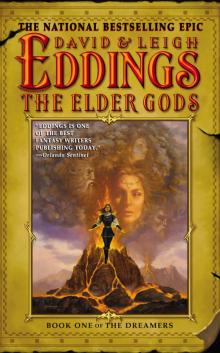

The Elder Gods Page 33

The Elder Gods Read online

Page 33

“Your canoe moves smoothly,” Longbow noted.

“I got lucky when I put this one together,” Red-Beard replied modestly. “I finally managed to get the right curve on the ribs. The one I built before was sort of skittish. Every time I sneezed, she’d roll over and dump me into the bay.”

“I’ve had the same thing happen to me a few times,” Longbow admitted. “Sometimes I think canoes have a warped sense of humor.”

Red-Beard tried to avoid looking at the towering cloud of smoke and ash spouting up out of the twin volcanos that blotted out most of the eastern sky, but he ruefully realized that he wasn’t going to make it go away by not looking at it. “Have you managed to come up with a way to pacify Sorgan yet?” he asked.

“Let’s try ‘emergency.’”

“You missed me there, I’m afraid.”

Longbow shrugged. “Zelana left in a hurry. Doesn’t that sort of hint that there might be a crisis somewhere that needed her immediate attention?”

“We can try it, I suppose,” Red-Beard said a bit dubiously. “Trying to persuade Hook-Beak that there’s something in the world more important than he is might be a bit difficult, though.”

“We’ll see,” Longbow replied as Red-Beard eased his canoe in against the Seagull.

“Did she finally decide to come home?” Rabbit called down to them from the Seagull’s deck. “If the cap’n doesn’t get the gold she promised him pretty soon, he might just start a whole new war.”

“We’d really rather that he didn’t, Rabbit,” Longbow called back. “Red-Beard and I’ve come to see if we can calm him down a bit.”

Rabbit pushed the rolled-up ladder off the rail, and it unwound its way down to the canoe.

Longbow took hold of the ladder. “It’s time to go to work, Chief Red-Beard,” he said with a faint smile.

“I wish you’d stop that, Longbow.”

“Just trying to help you get used to it, friend Red-Beard,” Longbow replied with feigned innocence.

Sorgan Hook-Beak of the Land of Maag was in a foul temper when Red-Beard and Longbow entered his cluttered cabin at the stern of the Seagull. “Where is she?” he demanded in a harsh voice. “If I don’t start handing out the gold I promised all these people back in Maag, things are going to start getting ugly around here. We did what she wanted us to do, and now it’s time to settle up.”

“We really can’t be certain just where she went, Sorgan,” Longbow replied. “Her Domain’s very large, and there might just be an emergency somewhere off to the north of here. When a fire breaks out somewhere, you don’t really have time to be polite before you rush off to put it out. I’m sure that as soon as she gets things under control, she’ll come right back.”

“I guess that sort of makes sense,” Sorgan grudgingly conceded. “Have you got any idea at all of where this new trouble might be?”

Longbow shrugged. “She didn’t bother to tell me. You know how that goes.”

“Oh, yes,” Sorgan said sourly. “She’s an expert when it comes to not telling people things they should know, I’ve noticed.”

“How very perceptive of you,” Longbow murmured. “I’m sure she’ll be back as soon as she’s dealt with whatever it was that pulled her away from here, but we’ve got another problem that’s a bit more pressing.”

“Oh?”

“The fire mountains up at the head of the ravine are still spouting, and I don’t think Lattash will be a safe place for anybody when the liquid rock comes boiling down the ravine. A flood of water’s bad enough, but a flood of liquid rock might be a lot worse, wouldn’t you say?”

“I’d say that it’ll go a long way past ‘might,’ Longbow. What should we do about it?”

“How does ‘run away’ sound to you?”

“Narasan tells me that the proper term is ‘retreat,’ but ‘run away’ sounds close enough to me.”

“We do have a bit of a problem, though,” Longbow continued. “Red-Beard’s uncle, Chief White-Braid, can’t quite accept the idea that the tribe will have to move away from Lattash. Red-Beard and I are sort of sneaking around behind his back right now, so we’d appreciate it if you didn’t mention what we’re doing if you happen to speak with him.”

“Old men get strange sometimes, don’t they?” Sorgan observed. “Don’t worry, Red-Beard. Your secret’s safe with me. When are you planning to pull off your mutiny?”

“Mutiny? I don’t think I’ve ever heard that term.”

“It’s something that happens on a ship when the crew gets unhappy with the captain. They either kill him or set him adrift in a small skiff. Then the leader of the mutiny takes command of the ship.”

“We don’t do that sort of thing here, Hook-Beak,” Red-Beard said firmly.

“Maybe you should give it some thought, Red-Beard,” Sorgan suggested. “If your chief is starting to lose his grip, somebody’s going to have to take charge before that boiling rock comes rushing down the ravine.”

“We can hope it doesn’t come to that,” Longbow stepped in. “Right now, Red-Beard and I need to find a suitable place for a new village. Most likely, it’ll be somewhere on down the bay—or even out beyond the inlet. It’ll have to have fresh water, open land for farming, and some protection from the wind and tides.”

“I gather that once you find it, you’d like to borrow my fleet to move the tribe to their new home?”

“If it’s not too much trouble,” Red-Beard agreed.

Sorgan shrugged. “It’ll give the other ship captains something to do beside coming here to the Seagull to complain about not getting paid. Besides, your people and their bows helped us a great deal in the ravine, so we’re more or less obliged to lend you a hand when you . . .” Sorgan stopped suddenly. “The gold!” he exclaimed. “Lady Zelana’s gold’s still in that cave! If that melted rock pours down over Lattash, it’ll fill up the cave, won’t it?”

“That’s not very likely, Sorgan,” Longbow disagreed. “Didn’t Ox shatter his ax when he tried to chop down that wall Zelana put up to protect the gold?”

“So that’s why she put that wall there,” Sorgan said. “We thought she’d put it up to keep us away from her gold, but it’s really there to keep the melted rock from oozing in and swallowing it, isn’t it?”

“It seems to be the sort of thing she’d do,” Red-Beard agreed. “Don’t worry so much, Hook-Beak. The gold’s perfectly safe, and I’m sure you’ll get paid just as soon as Zelana comes back. You might want to pass the word to the ship captains who spend all their time complaining. They will get paid, but right now Zelana’s off someplace in her Domain dealing with some new emergency.”

“That might just be the answer to your problem right there, Red-Beard,” Sorgan suggested. “When she comes back, you can tell her that your uncle’s not quite right in the head, and then she can set him aside and put you in charge. That’d be a lot better than a mutiny, wouldn’t you say?”

“It’s something to consider, Chief Red-Beard,” Longbow agreed.

Red-Beard scowled at him.

“What’s the problem, Red-Beard?” Sorgan asked. “The word ‘chief’s’ a lot like the word ‘captain,’ and I’ve always thought that had a pleasant sort of sound to it.”

“Not to me it doesn’t,” Red-Beard declared.

2

The wind coming in from Mother Sea was quite gusty, and that didn’t bode too well for Red-Beard’s plans to relocate the tribe. The village of Lattash was well sheltered from foul weather, and Red-Beard could almost hear the steady chorus of complaints he was certain the villagers would hurl at him every time he passed by if they were obliged to move out here.

The sun was already low over the western horizon, but due to the prevailing wind, Red-Beard and Longbow were only about halfway along the north side of the bay.

Longbow squinted toward the west. “We’re about to run out of daylight,” he noted. Then he looked at the shoreline. “Isn’t that a river just ahead?” he asked.

Red-

Beard looked at the beach. “I think you’re right, Longbow. The brush sort of hides it, but brush usually means fresh water. Let’s go have a look.” He turned his agile canoe toward the beach with a single backstroke.

“Are you at all familiar with the coast on this side of the bay?” Longbow asked as they smoothly paddled the canoe toward the beach.

“No. The fishing’s so good off the beach at Lattash that I’ve never had any reason to come this far out. Besides, I didn’t want to offend the local fish at Lattash by trying my hand somewhere else. Fish are very sensitive about that sort of thing, you know. They get miffed if you ignore them, and sulky fish don’t bite. Everybody knows that.”

“You’ve got a very warped sense of humor, friend Red-Beard.”

“How can you say that, friend Longbow? I’m shocked at you! Shocked!”

“Oh, quit.” Longbow peered at the brushy beach. “The river’s a bit larger than I thought. We might want to explore this area.”

“I don’t think the people of the tribe would care for the wind very much,” Red-Beard said dubiously. “Lattash is sheltered, but this area’s right out in the open.”

“Wind isn’t as bad as melted rock,” Longbow reminded him as they drove the canoe up onto the beach. “Let’s have a look at this river. If the water’s brackish, this wouldn’t be a good place for the new village, and we’ll have to move on. If it’s fresh, though, we might want to explore the surrounding countryside.”

“Lead the way,” Red-Beard agreed, and they fought their way through the wind-whipped brush toward the slow-moving river. “Isn’t it odd that the sun was going down just as we reached this place?”

Longbow shrugged. “Coincidence, probably.”

“There’s no such thing as coincidence, friend Longbow. That’s why we have gods. They make everything happen. If you happen to stub your toe, it’s because some god knew that you’d be following that trail someday, so just as a joke he put a rock in the middle of that trail along about the beginning of time. Gods are like that. They play tricks on us all the time.”

“Will you stop that, Red-Beard?”

“Probably not. I like absurdity. It makes life a lot more fun.” Red-Beard ducked under a stout limb that jutted out from a substantial bush. “All this clutter’s going to have to go if we move here,” he grumbled. “The women of the tribe will get very grouchy if they have to fight their way through this every time they go to the river for water.”

They reached the bank of the slow-moving river, and Longbow bent and scooped up a handful of water and tasted it. “Not as bad as it looks,” he said. “It’s a little muddy, but it should clear up later in the summer. When morning comes, we might want to explore the ground upstream. If there happens to be a meadow nearby, we should give this place some serious consideration.”

“Maybe so,” Red-Beard agreed, “but we should probably see if we can find some other places as well. That way, the tribe will be able to choose—and to argue. Arguments are good for people, did you know that? They stir up the blood, and lazy blood isn’t good for people.” He looked around. “I’ll put out some setlines,” he said. “If we’re going to dawdle around here on dear old windy beach, we’ll need something to eat.”

“Sound thinking,” Longbow agreed.

As the sun came up the next morning, it turned the cloud of smoke hovering over Lattash a bleary sort of red, almost as if reminding Red-Beard that Lattash wouldn’t be there much longer. That had been happening every morning since the twin mountains at the head of the ravine had ended the war, but Red-Beard was still unhappy about the whole thing.

He fought his way back through the brush to the river and pulled in the setlines he’d put out the previous evening. He was just a bit surprised at the size of the fish the untended lines had hooked.

“Not bad at all, friend Red-Beard,” Longbow said when Red-Beard carried his catch back to the campfire. “We might want to mention that when we get back to Lattash. If the fishing’s good around here, it might take some of the sting out of leaving the old village.”

“We’ll see. Why don’t you build up the fire while I clean these? Then we’ll have fish for breakfast.”

“Sounds good to me,” Longbow agreed, piling more limbs on the fire. “The wind seems to have backed off,” he observed.

“What a shame,” Red-Beard said. He held up the iron knife Rabbit had made for him. “This makes cleaning fish go a lot faster,” he observed. “Iron makes good tools. Let’s hope that Zelana will let us keep them after we’ve won all these wars and the Maags go home.”

“Why would she tell us to throw them away?”

“I don’t know—maintain the purity of our culture, maybe. She might not like the idea of contamination. Gods are strange sometimes.”

“You know, I’ve noticed that myself,” Longbow replied with no hint of a smile.

The fish were of a different variety than the ones that were common out in the bay, and they tasted very good. Red-Beard hoped that might help to persuade the members of the tribe that this would be a good place to live despite a fair number of drawbacks. It would never be as pretty as Lattash, and the constant wind would irritate the tribe almost as much as the thick brush and muddy river would.

After they’d eaten, Longbow stood. “Let’s have a look around,” he suggested. “So far we’ve found fresh water and good fishing. Let’s see what else this place has to offer.”

The morning light had a bluish tint to it as the two of them entered the forest that lined the upper side of the sandy beach. The trees were large, and they blocked off the perpetual wind that had made the beach so unpleasant.

“Deer,” Longbow said very quietly, pointing off to the right.

Red-Beard turned slowly. Quick movements usually startle deer.

It seemed to be a fairly large herd—two dozen or so at least—and there were quite a few spotted fawns grazing with the adult deer. “They look to be in fairly good shape,” Red-Beard noted.

“I’d say so, yes. Let’s ease on past them. There’s no point in disturbing them while they’re busy eating.”

The two of them moved on quietly through the damp forest. After about a half mile the light ahead seemed to grow brighter, a fair indication that there was a clearing in that direction.

When they reached the edge of the trees, Red-Beard saw that “clearing” was a gross understatement. The meadow beyond the trees extended for miles, and the stream they’d seen on the beach the previous day seemed to wander aimlessly through that meadow. The grass was very tall, and there was a sizeable herd of bison out there grazing in the gentle light of the morning sun.

“That answers that question, doesn’t it?” Longbow said. “It looks to me like there might be about five times as much land for farming as the women of your tribe will need right here.”

“At least five times,” Red-Beard agreed. “Those bison might be a bit of a problem, but we should be able to come up with a way to keep them out of the gardens.” He looked around with a certain satisfaction. “We might as well go on back to Lattash, friend Longbow. I don’t think we’ll find any place that’s better than this one.”

“Except for the wind,” Longbow added.

“The tribe can learn to live with the wind, I think. Good fishing, good hunting, and good farmland are the important things. This is the place.”

“You never know, friend Red-Beard. Perfection might lie just a few miles farther ahead.”

“I’m not really in the mood for perfection right now, friend Longbow. This place is good enough for me.”

“Spoilsport,” Longbow accused mildly.

It was about midmorning when they put Red-Beard’s canoe back in the choppy water of the bay, and the wind, which had slowed them on the previous day, was behind them now, so they made very good time.

Red-Beard felt a certain satisfaction. The constant wind and the thick brush along the riverbank were drawbacks certainly, but the advantages of the location far outweighed t

hem. The one thing that might help Chief White-Braid get over his sorrow was the lack of any serious mountains in the general vicinity. From what Red-Beard had seen, there was nothing that could really be called a mountain anywhere near the beach. There were rounded hills, but hills usually don’t catch on fire, and their gentle slopes wouldn’t encourage the spring floods which were such a nuisance in Lattash. All in all, it was a very good location, and if he could persuade his uncle that the tribe should move here, Chief White-Braid might set his sorrow aside and start making decisions again. That was Red-Beard’s main concern right now. Just the thought of being forced to accept the tedious responsibilities of chieftainship made him go cold all over. He enjoyed his freedom far too much to find much pleasure in the possibility of leadership.

It was late in the afternoon when they reached the harbor of Lattash, and Longbow looked back over his shoulder from his place in the bow of the canoe. “As long as we’re here anyway, let’s swing south a ways. I think we might want to have a word with Narasan.”

“We might as well, I guess,” Red-Beard agreed, veering his canoe toward the anchored Trogite fleet.

The sun was low over the western horizon, and it was turning the sky a rosy pink when they reached Commander Narasan’s wide-beamed ship. The young Trogite Keselo was standing at the rail with a worried sort of expression on his face. Keselo was very bright, Red-Beard had noticed, but he always seemed to take everything much too seriously. “Is there some sort of problem?” he called down to them as Red-Beard pulled his canoe in alongside the Trogite ship.

“Oh, nothing really all that serious,” Red-Beard replied, trying to sound casual. “The fire mountains are still belching, the village of Lattash is doomed, and it hasn’t rained for ten days. Aside from that, everything seems to be all right.”

“I really wish you wouldn’t do that, Red-Beard,” Keselo said with a pained expression.

“I think we should talk with your commander, Keselo,” Longbow said. “We seem to have a problem, and he might be able to come up with a solution.”

The Losers

The Losers The Ruby Knight

The Ruby Knight The Sapphire Rose

The Sapphire Rose King of the Murgos

King of the Murgos The Seeress of Kell

The Seeress of Kell Demon Lord of Karanda

Demon Lord of Karanda Pawn of Prophecy

Pawn of Prophecy Queen of Sorcery

Queen of Sorcery Castle of Wizardry

Castle of Wizardry Guardians of the West

Guardians of the West Sorceress of Darshiva

Sorceress of Darshiva The Shining Ones

The Shining Ones Enchanters' End Game

Enchanters' End Game Magician's Gambit

Magician's Gambit High Hunt

High Hunt The Hidden City

The Hidden City The Rivan Codex

The Rivan Codex Regina's Song

Regina's Song The Elder Gods

The Elder Gods The Malloreon: Book 02 - King of the Murgos

The Malloreon: Book 02 - King of the Murgos The Malloreon: Book 05 - Seeress of Kell

The Malloreon: Book 05 - Seeress of Kell Treasured One

Treasured One The Malloreon: Book 04 - Sorceress of Darshiva

The Malloreon: Book 04 - Sorceress of Darshiva The Malloreon: Book 03 - Demon Lord Of Karanda

The Malloreon: Book 03 - Demon Lord Of Karanda Belgarath the Sorcerer and Polgara the Sorceress

Belgarath the Sorcerer and Polgara the Sorceress The Malloreon: Book 01 - Guardians of the West

The Malloreon: Book 01 - Guardians of the West The Treasured One

The Treasured One Pawn of Prophecy tb-1

Pawn of Prophecy tb-1 Polgara the Sorceress

Polgara the Sorceress Belgarath the Sorcerer

Belgarath the Sorcerer The Younger Gods

The Younger Gods Crystal Gorge

Crystal Gorge