- Home

- David Eddings

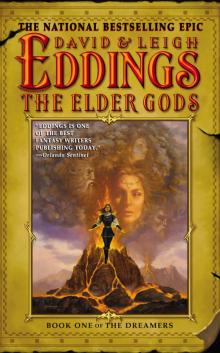

The Elder Gods Page 31

The Elder Gods Read online

Page 31

With Hook-Beak in the lead they splashed through the shallow stream to the other side of the river, even as Commander Narasan and Red-Beard scrambled up the riverbank toward the south bench.

“Rabbit!” Sorgan said sharply when they reached the north riverbank. “Scamper up to the bench just as fast as you can and tell all those men who were following Ox to get up to the rim of the ravine before the sides collapse and bury them alive!”

“Aye, Cap’n,” Rabbit replied, already running.

Hook-Beak, Keselo, and Longbow had just reached the north bench when the ground began to shudder violently again.

Longbow looked up the slope. “This way!” he told Hook-Beak and Keselo, already running toward a large boulder jutting up out of the center of the bench.

Rocks were rolling and bouncing down the north side of the ravine to spill across the bench in a thunderous landslide. The three men huddled behind their protective boulder, listening to the sharp crashing sound of large rocks slamming into the other side of their shelter.

“What were Veltan and Red-Beard talking about, Longbow?” Hook-Beak demanded. “What’s a fire mountain?”

“It’s a mountain that spews out melted rock,” Longbow explained. “I’ve seen a couple of them up in the lands of Old-Bear’s tribe.”

“Rocks don’t melt, Longbow,” Sorgan scoffed.

“They will if the fire under them’s hot enough,” Longbow disagreed, “and melted rock will run downhill just like melted ice will.”

The trek up to the rim of the ravine involved a series of short dashes from one slightly protected spot to another, with short pauses during the recurring earthquakes to permit the accompanying landslides to rush past.

Keselo was winded by the time they reached the rim, and he paused to catch his breath.

“Great gods!” Sorgan gasped, staring toward the east in stunned disbelief.

Keselo turned and saw dark smoke boiling up out of the twin mountains that formed the gap. Then there came another earthshaking explosion, and sheets of flame came spewing out of the two peaks in twin geysers of liquid fire, reaching up and up toward the sky and spattering the sides of nearby peaks with globs of molten rock.

“Run!” Sorgan bellowed to his men. “Get back away from the edge!”

The Maags were all gaping at the explosion at the head of the ravine.

“I said run!” Sorgan roared. “Run or die!”

Keselo leaned out over the edge to look briefly at the ancient ruin just below. A fountain of fire came spurting out of the hidden cave mouth, and it blasted the walls and towers far out over the river. The molten rock poured down the steep slope, and a vast cloud of steam boiled up into the air when the liquid rock reached the brook.

Keselo bolted, running as hard as he could toward the nearby mountains.

The twin eruptions continued for the rest of the day and on through the night. Hook-Beak’s forces gradually gathered together on the steep north slope of a nearby mountain, quite obviously in the hope that the mountain might shield them from the molten rock still spewing out of the twin mountains at the head of the ravine. Along toward morning, Ox, who’d been out gathering the straying Maags who’d survived the encounter with the snake-men and the sudden violent eruption, came wearily up the slope. “This was about as many as I could find, Cap’n,” he reported. “I’m pretty sure there’s more of them, but they’re probably way back in the mountains by now.”

“Did you come across any of the snake-men?” Sorgan demanded.

“Not so much as a single one, Cap’n,” Ox replied. “Since they ain’t none too smart in the first place, I’d say they probably tried to hide out in them nice safe caves and tunnels and burrows, and those are the last places anybody with any brains wants to be along about now. I’d say that the war’s over, Cap’n. All our enemies just got theirselves tossed into the cooking pot.” He frowned slightly. “I really hate to see all that fresh-cooked meat go to waste, but I don’t think I’d care much for fried snake.”

“I could probably get along without it myself,” Sorgan agreed with a grin. “Look on the bright side, though, Ox. As hot as rock has to be to start melting, all those dead snakes are probably way overcooked.”

“There is that, I suppose,” Ox conceded.

Longbow was standing off to one side, and he motioned to Keselo and Rabbit and led them some distance away from Sorgan and Ox. “Zelana wants to speak with us,” he told them quietly.

“It’s quite a long way back to Lattash,” Rabbit protested.

“She came up here,” Longbow explained. “She’s waiting back in the forest just a little ways.”

“How did she get word to you?” Keselo asked. “You’ve been right out in plain sight ever since we came up out of the ravine, and I didn’t see a sign of her.”

“Longbow and Lady Zelana can talk to each other without anybody else hearing them,” Rabbit explained. “A lot of that was going on in the harbor at Kweta when Longbow and I killed off some Maags who were trying to steal the cap’n’s gold blocks. That was a wild night, let me tell you.” Then Rabbit looked sharply at Longbow. “How far down the mountains will that melted rock go?” he demanded.

“Probably all the way down to Mother Sea. Why?”

“Won’t that destroy Lattash?”

“Probably, yes. I think Chief White-Braid’s tribe might have to find someplace else to live.”

“Probably so, but Lady Zelana has her gold stacked up in that cave just outside of town, and if this liquid rock happens to run into her cave, the gold will melt and get all mixed up with the rock, and the cap’n won’t get paid, will he?”

“Quit worrying so much, Rabbit,” Longbow said. “Zelana’s probably already moved her gold,” He looked around. “She’s right over there in that clump of trees. Let’s go see what she has to say.”

Zelana and Eleria sat side by side on a moss-covered log in the center of a clearing in the middle of the grove. “Is everybody all right?” Zelana asked as Keselo and Rabbit followed Longbow into the clearing.

“As far as we know, they are,” Longbow replied. “Did your younger brother happen to remember to warn Sorgan’s cousin Skell? Sorgan’s been worrying about that since yesterday.”

“Veltan warned Skell on his way up here, Longbow,” Zelana said. “Tell Sorgan that he worries too much.”

“Your younger brother cut things a little fine, Zelana,” Longbow declared. “He should have warned us earlier.”

“That was Yaltar’s fault,” Eleria told him. “I think his volcano got away from him. Vash tends to overdo things now and then.”

“Who’s Vash, baby sister?” Rabbit asked.

“Did I say Vash?” Eleria asked. “I meant Yaltar, of course.”

“Yaltar was angry, Eleria.” Zelana excused Veltan’s little boy. “Those caves and burrows took us all by surprise, and Yaltar doesn’t like surprises, so he overreacted.”

“Then the earthquakes and all of that melted rock were sort of like Eleria’s warm wind?” Rabbit suggested.

“My wind wasn’t nearly as nasty as Yaltar’s volcano, Bunny,” Eleria sniffed. “Boys are so noisy. They just have to show off when they do something.”

“His liquid rock did seal up the Vlagh’s caves and burn up all the snake-men in the burrows, baby sister,” Rabbit reminded her. “We were in a lot of trouble before those twin peaks up at the gap exploded.”

“There’s something I don’t quite understand, ma’am,” Keselo said to Zelana. “If you and your family are able to unleash these catastrophes, why did you go to all the trouble and expense of hiring armies to fight this war for you? Why didn’t you just go ahead and deal with your enemies by yourselves?”

“It’s just a little complicated, Keselo,” Zelana replied. “That- Called-the-Vlagh created its servants by the thousands, so they vastly outnumber the people of the four Domains, and they’re very savage. Our people aren’t nearly as numerous as the creatures of the Wasteland. When we learn

ed that the Vlagh was about to unleash the monsters of the Wasteland on our Domains, we knew we were going to need help, so my brothers, my sister, and I went out to other lands to buy that help with gold. We didn’t really understand at that time just how far the Dreamers could go. My family and I are limited by certain constraints. I’m sure that none of us could have unleashed that volcano the way Yaltar’s dream did, or caused the flood Eleria’s dream set in motion. Our minds don’t work that way. The dreams don’t have limitations, though. They’re based on imagination—or possibly inspiration—not reality.” She paused. “Is this making any sense to you at all, Keselo?” she asked him.

“Not really, ma’am,” he admitted.

“I’m sure it’ll come to you in time,” she said with a faint smile.

“Things got a little exciting there for a while,” Rabbit was saying to Zelana. “We were all fairly certain that we were up against a bone-stupid enemy, but they’re not nearly as ignorant as we’d thought. If it hadn’t been for that fire mountain, we’d have been in some real trouble.”

“It’s easy to underestimate the intelligence of the creatures of the Wasteland, little man,” Zelana replied. “As individuals, they’re stupid beyond belief, but as a group, they have a surprising intelligence. They have many ways to communicate with each other. Some of them speak, but others are more elemental. Unlike you man-creatures, they tell each other everything they’ve encountered, and those who receive that information share it with still others. Everything that any one of them has seen or experienced becomes the possession of all members of the group, and the group is wiser by far than the individual members. The ultimate decisions are made by That-Called-the-Vlagh, but I think that the Vlagh itself is to some degree susceptible to the dictates of that overmind. They will most probably surprise you many times. I know they’ve surprised me quite a few times already, and that hasn’t made me very happy.”

“What we really need, then, is some way to disrupt their communication with each other, wouldn’t you say?” Keselo suggested. “Loud noise, maybe, or dense smoke, or possibly odors of some kind.”

“Odors is something we should really investigate,” Zelana agreed. “If something smells bad enough, it might very well interfere with their ability to communicate with each other. I’ll speak with my brothers and my sister about it.” She paused and then moved on. “The servants of the Vlagh have been blocked in my Domain, but there are still three more Domains that need protecting. I’m almost positive that Dahlaine and Aracia will need help as much or more than Veltan and I. What I’m getting at, gentlemen, is that I’m sure that we’ll need Hook-Beak and Narasan for much longer than we’d originally anticipated.”

“I’m not too sure that the cap’n will buy into a long war,” Rabbit said dubiously. “He’ll help Commander Narasan because the Trogites helped us, but that might be about as far as he’ll be willing to go. Once we win Narasan’s war, the cap’n might just decide to take his gold and go on back home.” The little fellow paused reflectively. “We Maags aren’t really all that good at land wars,” he admitted. “All this slogging around in the mud, sleeping on the ground, and eating cold food sort of goes against our grain. We like short, noisy wars that’re over by suppertime.”

Zelana shrugged. “The offer of more gold will probably persuade Hook-Beak that land war’s not really all that bad.”

“Gold’s nice,” Rabbit countered, “but you’ve got to live long enough to spend it. I’m not sure how Keselo felt about what happened in the ravine, but it scared me silly.”

“It sort of made my hair stand on end as well,” Keselo admitted. “I’ve been on the opposite side of the ravine from Commander Narasan for quite some time now, so I’m not exactly sure how he feels about what happened here, but he might be starting to have second thoughts. Those serpent-men who were trying to kill us aren’t intelligent enough to be afraid. Usually, we Trogites feel that a stupid enemy is a gift from the gods, but if the stupidity goes far enough to eliminate fear, it might have caused the commander to have second thoughts about this whole arrangement. A key element in any war strategy is undermining the enemy’s morale. A frightened man will usually just give up and run away. An insect or a serpent doesn’t know how to be afraid, though, so many standard Trogite tactics just won’t work.”

“I want you gentlemen to think very hard about this,” Zelana said firmly. “You need to come up with some way to persuade your leaders to stay here and help us. If you can’t, I might just have to burn all their ships to keep them here, whether they like it or not.”

“We should get back,” Longbow told Keselo and Rabbit. “Hook-Beak might miss us, and I don’t think we want any Maags to come looking for us. They don’t really need to know anything about this discussion, do they?”

“Not if we’re going to keep talking about burning ships, they don’t,” Rabbit agreed.

Keselo was profoundly troubled as he lay wrapped in his blankets some distance from the fires in the encampment of the Maags. The thunderous eruption of the twin volcanos at the head of the ravine was subsiding, and there was much cheer in the ranks of Hook-Beak’s army. The Maags continued to marvel about “the greatest stroke of good luck in history” as if the eruption had been nothing more than sheer coincidence.

Keselo, however, knew better, and he profoundly wished that he didn’t. Zelana’s coldly brutal evaluation of the situation here in the Land of Dhrall chilled Keselo to the bone. Although she was beautiful beyond belief, there was a rock-hard practicality at her center, which only Eleria could soften, and Eleria, when the situation required it, was even worse.

The Dreamers could unleash natural disasters far worse than the ordering of armies into hopeless struggles and threatening to burn the ships that were the only hope of escape those armies had.

Worse yet, the soldiers, ignorant of what was truly happening, were cheering.

Keselo, however, had gradually come to perceive the true nature of That-Called-the-Vlagh. Driven by an uncontrollable need to possess the entirety of the Land of Dhrall and surrounded by countless nonhuman servants, the Vlagh would pursue its need despite defeat after defeat after defeat, giving no thought to the vast number of servants it would inevitably lose. Even worse, perhaps, was the fact that the Vlagh did not function solely on instinct. There was an evil cunning there, which in the end might very well overcome them all—human or divine.

And now the Maags and Trogites were effectively trapped here in the Land of Dhrall, doomed to fight a dreadful war that they could not possibly win, given the overwhelming numbers of their enemies.

THE PINK GROTTO

1

Eternal Zelana was filled with unspeakable horror and an overwhelming sense of guilt at the chaos unleashed by the Dreamers. It had seemed at first that her elder brother’s solution to the current crisis had been the perfect answer. Eleria’s flood and Yaltar’s volcanos were natural disasters, after all, and nobody was really to blame for them, were they?

It had seemed so to Zelana at first. Her Domain had been threatened by the creatures of the Wasteland, and now the threat was gone. None of the events in the ravine had been the result of anything she had personally done, so why was she now filled with this wrenching sense of guilt? No matter how many times she said to herself, “I didn’t do any of this,” the accusing finger at the back of her awareness continued to point directly at her.

Slowly, reluctantly, she was finally forced to face a dreadful reality. The disasters unleashed by the innocent Dreamers had been a response to her needs. It was becoming increasingly clear that the children could somehow sense what she wanted, and their dreams provided it. The dreams were gifts, in a certain sense, but they carried with them a dreadful burden of responsibility, and try though she might, Zelana could not shrug off that burden.

And so it was that finally, without so much as saying a word to her brothers or sister, Zelana of the West took her beloved Dreamer Eleria in her arms and fled.

“What

are we doing, Beloved?” Eleria cried, clinging to Zelana in fright as they rose up and up through the smoky midnight air toward the pale moon.

“Hush,” Zelana told her as she searched with her mind and senses for an eastward-flowing wind.

Far below them Zelana could see Yaltar’s cursed volcano spewing molten lava high into the air, and the glowing river of liquid rock surging down the ravine toward the village of Lattash. “Idiocy!” Zelana fumed, still rising and searching.

“Please, Beloved!” Eleria cried. “I’m afraid!”

“Everything’s all right, dear,” Zelana told the child, trying her best to sound calm.

“Where are we going?”

“Home,” Zelana replied. “I’ve had about enough of all this, haven’t you?”

“Do we have to go up so high?” Eleria cried, clinging desperately to Zelana.

“Hush, Eleria. I’m trying to concentrate.”

It was hardly more than a fitful breeze, but it was moving in the right direction, so Zelana seized it, and they moved haltingly through the spring night, away from the horror below them.

Once they had moved out beyond the west coast of the mainland, the breeze grew stronger, and it carried them across the straits to the coast of the Isle of Thurn. Zelana thanked the breeze, and she and Eleria drifted south through the moonlit air toward the stark cliffs on the southern margin of the Isle.

“The world looks different from up here, doesn’t it, Beloved?” Eleria said. She seemed a bit calmer now, and she relaxed her desperate grip somewhat. “This is quite a bit like swimming, isn’t it?”

“A little bit, yes,” Zelana agreed. “You do know why we absolutely had to come away, don’t you?”

“Well, not entirely, Beloved,” Eleria admitted. “Is something wrong?”

“Everything was wrong, Eleria. Things weren’t supposed to happen the way they did.”

“We won, didn’t we? Isn’t that all that really matters?”

“No, dear, dear Eleria,” Zelana replied, tightening her embrace about the child. “We lost much more than we won. The Vlagh stole our innocence. We did things we weren’t supposed to do, and nothing will ever be the same again.” She peered down at the south coast of Thurn. “There it is,” she said when her eyes found a familiar beach glowing in the moonlight. “Let’s go home.”

The Losers

The Losers The Ruby Knight

The Ruby Knight The Sapphire Rose

The Sapphire Rose King of the Murgos

King of the Murgos The Seeress of Kell

The Seeress of Kell Demon Lord of Karanda

Demon Lord of Karanda Pawn of Prophecy

Pawn of Prophecy Queen of Sorcery

Queen of Sorcery Castle of Wizardry

Castle of Wizardry Guardians of the West

Guardians of the West Sorceress of Darshiva

Sorceress of Darshiva The Shining Ones

The Shining Ones Enchanters' End Game

Enchanters' End Game Magician's Gambit

Magician's Gambit High Hunt

High Hunt The Hidden City

The Hidden City The Rivan Codex

The Rivan Codex Regina's Song

Regina's Song The Elder Gods

The Elder Gods The Malloreon: Book 02 - King of the Murgos

The Malloreon: Book 02 - King of the Murgos The Malloreon: Book 05 - Seeress of Kell

The Malloreon: Book 05 - Seeress of Kell Treasured One

Treasured One The Malloreon: Book 04 - Sorceress of Darshiva

The Malloreon: Book 04 - Sorceress of Darshiva The Malloreon: Book 03 - Demon Lord Of Karanda

The Malloreon: Book 03 - Demon Lord Of Karanda Belgarath the Sorcerer and Polgara the Sorceress

Belgarath the Sorcerer and Polgara the Sorceress The Malloreon: Book 01 - Guardians of the West

The Malloreon: Book 01 - Guardians of the West The Treasured One

The Treasured One Pawn of Prophecy tb-1

Pawn of Prophecy tb-1 Polgara the Sorceress

Polgara the Sorceress Belgarath the Sorcerer

Belgarath the Sorcerer The Younger Gods

The Younger Gods Crystal Gorge

Crystal Gorge